In Politics and the English Language, George Orwell remarked that “political speech and writing are largely the defence of the indefensible.” This is an apt job description for California Attorney General Xavier Becerra in his role as draftsman of California ballot language.

Becerra is tasked with writing the titles and summaries that appear on our ballots. But rather than accurately describe the Propositions, he's made a habit of “skewing the language in favor of one side” (SF Chronicle), “tricking the electorate” (San Jose Mercury News), and “forsaking impartiality” (LA Times).

The Mercury News notes that Becerra's predecessor, Kamala Harris, "played the same game," and this suppressed worthy measures from appearing on the ballot at all.

Calling this fraud is not hyperbole. That's literally what it is, from the state’s top lawyer no less. The California Civil Code defines fraud as follows:

“an intentional misrepresentation, deceit, or concealment of a material fact known to the defendant with the intention on the part of the defendant of thereby depriving a person of property or legal rights or otherwise causing injury”

For the twelve Propositions on our ballots, several of Becerra’s titles meet this definition. Let’s examine two of them, by comparing Becerra’s title with the description given by the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst – who I’ve argued should take over the job.

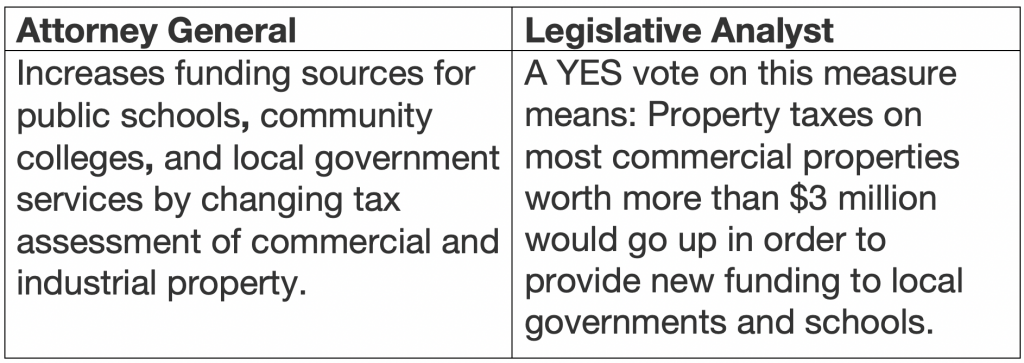

Prop. 15: Property Taxes

This is the initiative to go after the classic Prop. 13. It is funded by the same special interests that have funded Becerra's campaigns.

Returning to the definition of fraud, Becerra has intentionally concealed not only a “material fact” but the single operative effect of the initiative – that taxes “would go up,” as the Legislative Analyst puts it.

As to the "injury" element of fraud, California business property owners will suffer most directly, though of course the increased costs will spread to all Californians.

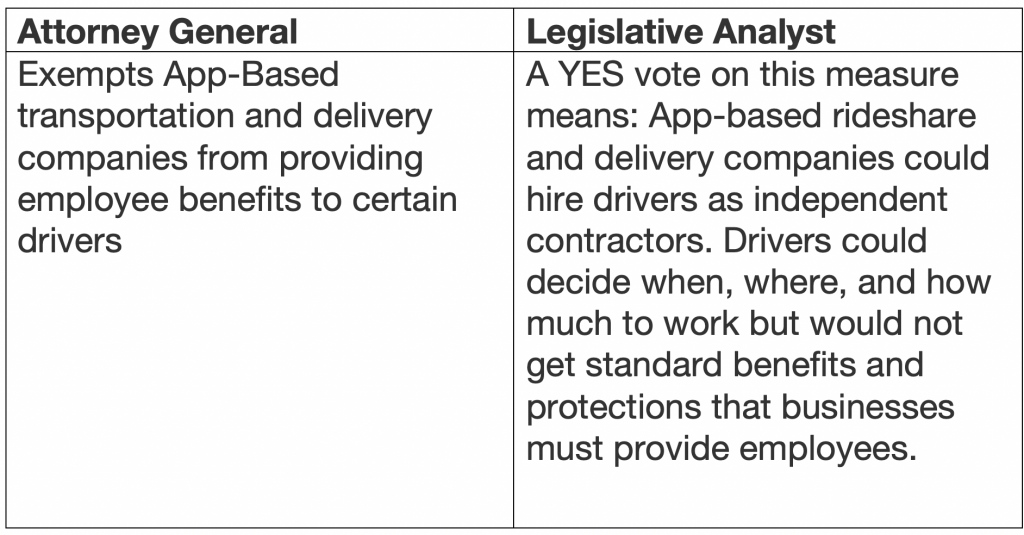

Prop. 22: Ridesharing

This is the initiative to reverse Assembly Bill 5 for the likes of Uber and Lyft drivers. The Proposition is opposed by special interests that have funded Becerra's campaigns.

Notably, Becerra did not recuse himself from writing the ballot title even though he’s currently suing Uber and Lyft under the very law they’re seeking to reverse.

Once again, the case for fraud is open-and-shut: Becerra willfully conceals that the affected drivers have chosen to forgo some benefits in return for the flexibility described by the Legislative Analyst: to “decide when, where, and how much to work."

The “injury” element of the fraud offense is also clear, as drivers who value that flexibility will be deprived of it – not to mention that millions of Californians could lose access to ridesharing if the companies are forced to leave the state.

So no, the charge of election fraud is not made in a figurative sense. In truth, it immensely understates the gravity of Becerra's offense. With ordinary fraud, the injury accrues to a private party. Here, it is the California public that is defrauded – not only as to the effect of a particular initiative, but as to a false sense of political agency.

That’s what’s most insidious about the perversion of direct democracy by Xavier Becerra and before him Kamala Harris: it's a denial of popular sovereignty. Turning ballots into Orwellian documents, with election outcomes baked in by politicians, poses fundamental problems of political legitimacy.

It’s more than just fraud. It’s a coup d'état.